Arctic Spine Race 2024

Rob Brooks

I’m lying face down on the ground under 3 feet of snow, it’s -30 degrees Celsius and I’m unable to move.

Moments before I had been descending from the Tjäktja Pass on cross country ski’s pulling a pulk behind me. I was fully in control and everything was going well .. until it wasn’t. Until I built up to a speed I wasn’t able to control, lost control and fell face forward into the deep snow.

My pulk was still attached to me and now thanks to gravity and the steep terrain was pinning me to the ground.

To complicate the situation further my skis were both still attached to my feet and also buried under the snow and the pulk, preventing any movement of my legs.

Welcome to the Arctic Spine, a 293 mile race along the Kungsleden Trail in Swedish Lapland in the depths of winter.

Pre race nerves

This race has been a long time coming. I went on a weeks training course with Phil Hayday-Brown, the mastermind behind this race and the UK Spine, and a few others 2 years ago in around the same area the race was due to take place. It was supposed to happen last year but there were only 2 of us entered so was unfortunately cancelled.

As the race drew ever closer and it became apparent that it would definitely go ahead my excitement and trepidation grew in equal measures.

There were times when I’d worry that I’d made a terrible mistake and was completely out of my depth. In these moments I tried to rationalise my fear – what exactly was it that I was so nervous about?

Although I wasn’t as fit as I’d have liked to be (when are we ever), fingers crossed this shouldn’t be a limiting factor.

I’d been on the training course and practiced all the skills I’d need in the race. I’d also pulled a home-made pulk around the Cairngorm plateau camping in freezing conditions and practiced up there with all my kit.

I’d completed the UK winter spine twice along with various other ultras and multi day events such as Dragons Back, the Itera Expedition Race and a Bob Graham Round so I had all of that experience to draw from.

I went through all the bad scenarios I could think of in my head and worked them through. What could I do to reduce the risk of them happening or if they did how could I reduce the impact of them, how could I get myself out of the situation.

I suppose a lot of it was fear of the unknown. It was the inaugural running of the race, and it wasn’t just a new race it was a new type of race. There are other cold weather races such as the Yukon Arctic Ultra, Lapland Ultra, 6633 and Arrowhead. These races however take place on well-groomed snowmobile tracks, dog tracks and even roads and are mostly flat so good progress can usually be made – people generally wear running shoes. They also have regular indoor support points where competitors can sleep and are provided with a hot meal.

This race was different, self sufficiency was the key. There were 3 checkpoints en-route where we would have access to a drop bag and be provided with hot water and fuel resupply but that was it. Sleeping would be outside in our tents as it would be anywhere else on the trail.

The route wasn’t flat either, it went through several mountain ranges rising up to 1150 metres at its highest point with about 24,000ft of climbing. Some of the route would be on snowmobile trails but most of it wouldn’t so breaking trail was a real possibility. At this time of the year we would have more than 16 hours of darkness each day to contend with.

There was no data from previous races to draw from – no previous competitors to compare notes or race strategies, no Facebook groups full of advice (maybe that’s not such a bad thing), no idea if the race was even possible.

In this day and age apart from the depths of the ocean the entire globe has been traversed and there are no new frontiers to explore. This race seemed like the closest I would ever get to true adventure and exploration and I felt incredibly excited and privileged to be in such a position.

Ultimately though if Phil didn’t think I was capable of competing in the race he wouldn’t have let me enter and I drew some comfort from that.

My pre-race plan had been to move for around 18 hours a day with 6 hours of “rest”. 3 hours of sleep plus time either side of that to make camp, melt snow eat and dry wet kit. This meant covering 36 miles a day and moving at around 2 miles an hour. Although this sounds easy my previous experience out here told me otherwise and I although didn’t feel confident I was certainly up for the challenge.

Pre race packing was fun trying to fit all of the gear and 14kg of food into my bags. The say pack your fears but I’ve never understood how packing a case full of spiders would be of any use and in any case I couldn’t fit them in anyway.

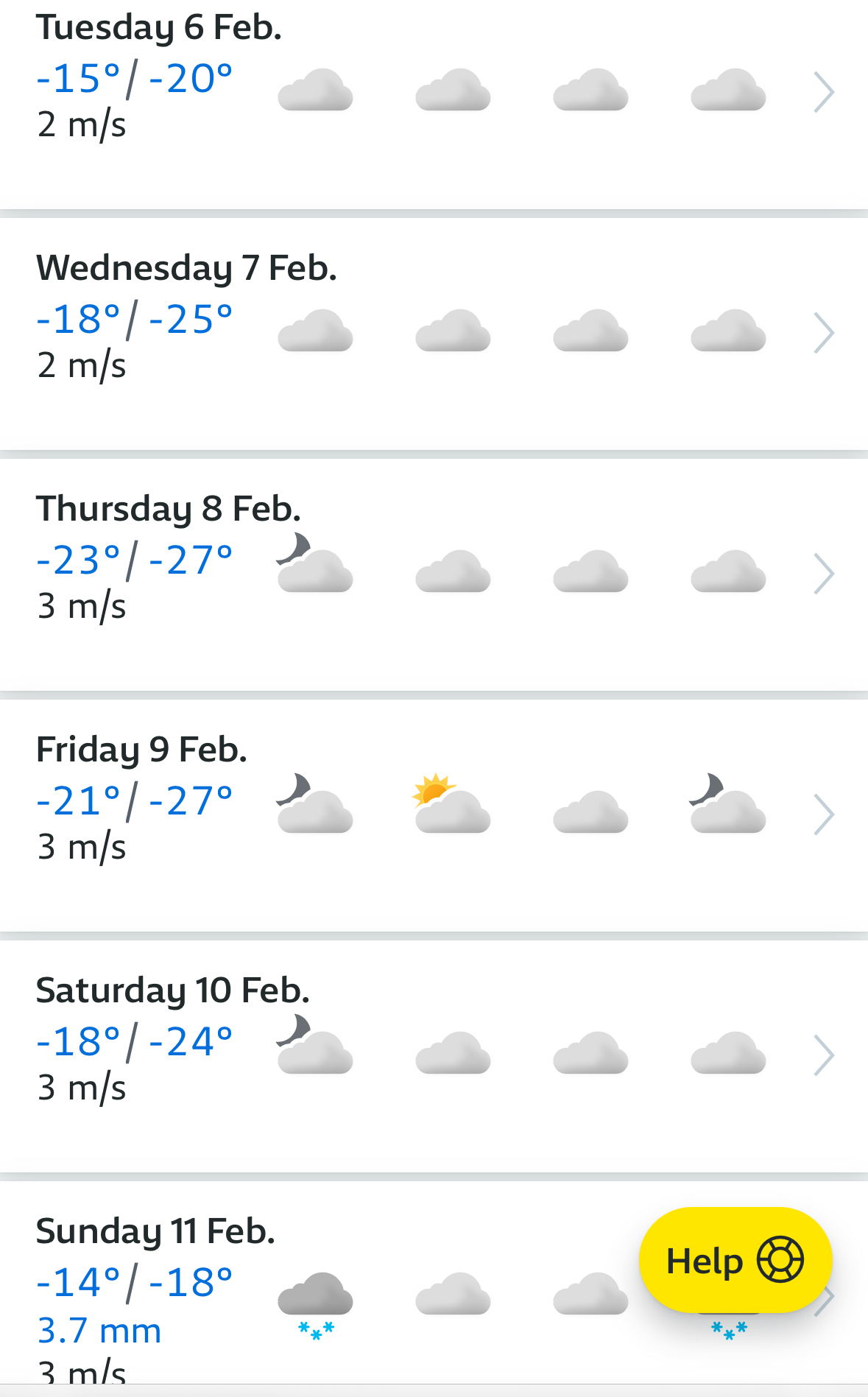

|

|---|

| The forecast for the week ahead was settled but cold |

Arrival in Abisko

The journey to Abisko was an adventure in itself. After 2 flights, a delayed 17 hour train journey and 2 car rides I finally arrived, 30 hours after leaving home in Gateshead.

Upon arrival at the STF (Swedish Youth Hostel) Phil showed us to our accommodation – we had our own log cabin with 5 beds, catering facilities and plenty of room for kit faffing.

|

|---|

| Home for the next few days |

I was sharing with Dutch athletes Robi Dattatreya and Robin Imthorn, who I’d met at the train station, and also Mael Jouan from France.

I also caught up woth Rob Hopkins with whom I’d been on the training course and was the only person other than myself to have signed up for the race last year.

Our hire kit (ski’s and pulks) wasn’t ready yet so I had a leisurely stroll along to the main village and purchased some last minute supplies from the well-stocked supermarket.

Upon returning I discovered Robin had been moved to a separate room to isolate as he’d been suffering from a nasty cough and a decision would be made tomorrow whether he would start the race (unfortunately he didn’t).

Myself and Robi then frequented the STF restaurant where we were joined by Kev Leahy and Joe Barrs and discussed pre race strategies over some tasty Reindeer Steak.

The next day was assessment day.

There were 14 of us in the race (sadly Robin wouldn’t be one of them) and 14 people on the support team (excluding the Sami who would be ferrying people around on snowmobiles and acting as search and rescue).

We then went through the dreaded kit check with every item being pored over and scrutinised in fine detail before moving outside and being assessed putting up our tents in the snow and using our stoves.

|

|---|

| Putting the tent up in the snow |

|

|---|

| Not a bad view |

John Bamber emphasised the importance of wearing gloves when handling fuel. If fuel comes into contact with naked flesh in freezing conditions the warmer skin causes the fuel to evaporate, and this subsequently has a cooling effect on the skin. If the air temperature is -30, the skin will cool to -40. Its instant frostbite.

Finally we were given a very serious race briefing with lots of scary terms such as frostbite, hypothermia, avalanches and death being thrown around although the mood was lightened upon lead medic Charlotte’s warning of the arctic elephants (you had to be there).

There were more kit faffing opportunities before we all gathered for a buffet meal together in the restaurant and then headed back for an early night.

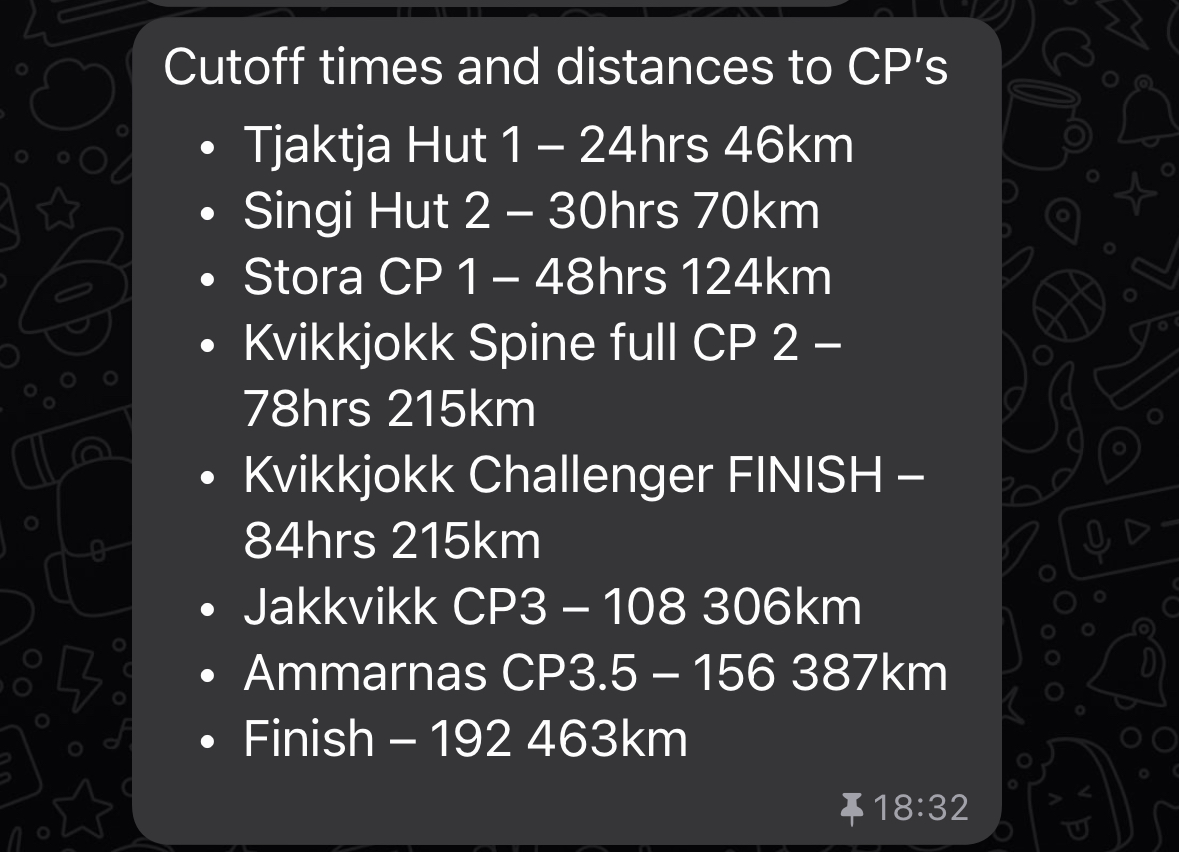

|

|---|

| Race cutoffs |

Finally getting started and an early catastrophe

|

|---|

| The start of the Kungsleden |

After breakfast and some last-minute faffing finally everyone was on the start line. A few photos, a motivational speech by Phil and we were off.

We started through a funnel which led to a slight downhill and a few people fell down at this point – I narrowly managed to dodge the carnage and escape unscathed. Up ahead Kev, Barclay Morison and Joe had sped off and because of the bottleneck behind I found myself in the strange position of being alone on the trail.

A few miles in and the birch woodland cleared revealing a vast panoramic view of the mountains into which we were heading. I stopped to take a few pictures at which point team Uhuru (Ed Sellon, Alexander Allen and Angus Currie) passed me and the others caught up so I was back in the pack.

We crossed a river and proceeded on a well groomed snowmobile track. Phil had told us not to blindly follow the GPX track so I knew that we wouldn’t be on top of it but we seemed to be veering further away from it which made me a little uncomfortable.

When the trail didn’t show any signs of returning to the gpx I stopped to check the map and realised that we had in fact taken the wrong turn and were now on the wrong side of the river heading into the wrong valley, shit. I cursed for making such an error so early on I the race.

We all stopped and I chatted though options with Eion, there was another trail marked on the map heading towards where we needed to be but it stopped short of the river and there were no bridges marked on the map so we’d have to beeline it and hope it was frozen.

The other option was retracing our steps back to the river crossing which I estimated to be about 30 minutes back and wasn’t an appealing prospect.

We decided on the former

At this point there were 7 of us – myself, Eoin, Charlie Wilkins, Caroline Barrett (team Exmoor Mountain Rescue) , Robi, Malou, and Andrew Bond. Uhuru had made the same mistake but they were out of sight ahead so we couldn’t call them back.

The trail was quite rough and steep in places, definitely not conducive to pulling a pulk but progress was ok until we reached the end of the train at a small cabin and a bridge.

It was now pretty much a case of making a beeline, but the deep snow and thick birch forest made for torturous progress, and we all took it in turns to break trail at the front.

We reached the river, only to find that it was in free flow and not frozen over, shit. We decided to flank the river upstream in the hope of finding a safe crossing at some point.

After a while we came to a snow bridge which looked like it was navigable, so we nervously crossed it in single file.

We were back on the GPX track now, but unfortunately is marked the summer trail and not the winter trail which took a slightly longer route and was further away.

There are lots of instances en-route where the summer and winter trails diverge. The winter trails are traversed by snowmobiles and skiers and as such generally take lower level more easily traversable routes.

In this instance the summer route contoured the side of a steep wooded valley whereas the winter route took a longer but flatter route around the outside of it.

We could either pick up the winter route further back or push on the summer route and convene with it further down. We decided on the latter and were again breaking trail over rough terrain.

On a number of occasions, we had to cross narrow wooded boardwalks straddling small frozen streams. It was a constant battle to prevent the pulks from slipping off the boardwalks, and we collectively worked as a team to help each other and make sure our pulks were aligned and didn’t fall off.

Eventually we hit our final barrier before joining the winter trail – a small suspension bridge to cross with steep steps on either side. Ski’s had to be taken off and a combination of man hauling, pulling, pushing and carrying got us all safely to the other side and back on track.

Seeing the red crosses that marked the trail again was a very welcome relief.

Back on track and into the night

After the previous adrenaline packed hours the group settled into a more steady pace and started to thin out. We reached the first frozen lake and caught a glimpse of the impending mountains ahead which were now much closer.

I had been feeling pretty sluggish up to this point but the steep climb up to the mountain plateau seemed to invigorate me and I made good progress.

The wind picked up a little and I zipped my coat right up to give some respite. The front of the coat covered over my mouth which kept it warm, but unwittingly I started breathing into it – this was the first in a long line of mistakes I’d make in the race.

One of the aspects which makes these types or adventures so challenging is the amount of time it takes to do anything. Anything that involves any type of dexterity (which is almost everything) means taking off the big gloves at a minimum which also means stopping as the gloves are attached to my poles through the straps.

Getting items out of pockets isn’t too bad, but if I need to reach anything in my rucksack it needs to be removed which means unhooking the straps attaching my gloves to my wrists otherwise they end up in a tangled mess.

If I want to sit anywhere the only option is my pulk which means straddling it and is extremely uncomfortable. Otherwise I need to remove my ski’s which aren’t too bad to get off, but the bindings often clog up with snow and ice getting them back on and is especially challenging in deep snow.

At one point I took my gloves off completely and lay them on the snow whilst I faffed with my pulk. By the time I put them on they were like icicles and my fingers were freezing. I left them on for probably a little longer that I should hoping they would quickly warm up once back on my hands. They didn’t.

I took them off and put them inside my coat to try and warm them and donned a thinner mid layer pair.

After around 15 minutes they were warm enough to put back on and I berated myself for such a stupid mistake. Sadly a few hours later I made the same mistake but this time the damage was irreversible, they were frozen solid so I swapped them out for my big thermal mitts.

Darkness arrived and I was rewarded with a beautiful starry sky, I’ve never seen the sky so beautiful. I stopped a few times just to take it in, there was not a breath of air and not a noise to be heard, only endless silence and solitude.

Even in the most remote parts of the UK at night you can usually see artificial light of some description, whether it’s a far-off settlement, a radio mast or a road.

Here there was nothing, just the awe-inspiring night sky and a sense of true isolation and raw beauty.

I was now alone so had the night sky all to myself. I occasionally glanced back and spotted headtorches, but it was impossible to tell how far away they were.

The route followed a snowmobile track which occasionally diverged causing confusion. There was only route marked on the map so I assumed that they would reconvene at some point which they generally did.

Due to my earlier mistake of breathing into my coat the top 5 inches or so were now covered in ice which rendered the zip useless and impossible to operate past the bottom of my neck so I donned an extra buff.

After a while I spotted some objects lying on the trail – a tracker and a few small bags, they must have fallen off someone’s pulk. I picked them up in the hope that I’d be able to re-unite them with their owner at some point.

On and on into the night I pressed. As I climbed further the sky clouded over and the wind picked up which had a dramatic cooling effect and a bank of wispy clouds closed in and obscured the night sky

I spotted a flickering light ahead which I hoped marked the Tjaktja Fjallstuga (a small mountain hut) in which I’d be able to get some hot water and be given a medical check (although sleeping wasn’t allowed).

It was impossible to tell how far away it was and after about an hour it didn’t seem to be getting any closer. And then I spotted a couple of other lights. Maybe they were from people in the hut.

They came ever closer until I was able to make out the outlines of 2 people pulling pulks. I was surprised that anyone else would still be out at this time as it was well past midnight.

It was Kev and Barclay. “Are you going to hut 1” they asked.

“Yes I am , where are you going?”

“We’ve been to hut 1, going to hut 2 now. You’re going the wrong way”

Shit, really how could that have happened? I couldn’t process it. I’d been carefully tracking my progress on my watch and cross referencing with my map to avoid a repeat of the previous morning’s excitement. Also, how could I have gotten in front of Kev and Barclay without seeing them or passing the hut.

I double checked my watch and map – “I’m pretty sure I’m going the right way – are you sure you haven’t doubled back on yourselves after the hut” A check of my compass confirmed I was going south, and they were heading north.

Kev checked his GPS “Shit you’re right we’ve doubled back on ourselves”.

After a bit more chat it transpired it was Kev’s tracker and kit I’d found on the trail so I was able to return them to him and we all headed up to hut 1.

|

|---|

| Hut 1 in daylight although it was dark when I was there |

Entering a checkpoint in the UK Spine race you are greeted by a team of people mothering you – taking your shoes off your feet, offering you a comfortable seat next to a roaring fire and offering you refreshments. Tea of coffee? Do you want some lasagne, some chicken curry? How about a bacon sandwich or a full English breakfast. How are your feet, can I help tape them for you whilst you relax and eat your bacon sandwich, or maybe have a quick snooze? How about a nice comfortable bed?

Entering the hut (actually a tiny room about the size of the emergency huts in the Cheviots) I was greeted by John Bamber who offered to defrost my water bottles, put some hot water into a dehydrated meal and James the medic who checked my hands for signs of frostbite. There was an outside long drop toilet with a metal seat if I needed it.

It wasn’t much warmer inside the hut that it was outside, intentionally so. Everyone was covered in snow, above 0 degrees snow turns into water. Once back outside water turns to ice and gets into places you don’t want it to get into, like zips rendering them useless.

Luckily my weren’t showing any signs of frostbite, but Joe (Barrs) who had arrived before me wasn’t so lucky. He was showing worrying signs in one of his fingers and was trying to rewarm them with some hand warmers and a big pair of insulated mitts.

The prognosis from James wasn’t great.

“Either you can stay here and be extracted via snowmobile, or you can push on to hut 2 and have them assessed there. Extraction from there will be a lot quicker. If you do that though under no circumstances can you let that had get cold again or your risking frost bite. “

I packed up my gear and left Joe to agonize over his decision. I really felt for him, he’d been leading the race and said that the felt amazing and was rearing to go but pushing on would be a big risk. It’s one thing to push on with a gammy ankle, some blisters or a muscle/tendon strain but quite another to risk losing a finger and it again highlighted the seriousness of the race.

A new dawn and a fall

It was about 3km from the hut to the top of the pass (the highest point of the race at 1150m) where there was another emergency shelter. I wasn’t originally planning on stopping there, I didn’t even know if it would be open but it was and although containing little more than a few benches and a table was certainly more inviting than camping in the snow so I decided to rest for a while and see if I could catch a few hours sleep.

It was around 4:30am so if I continued any further it would almost certainly mean sleeping in daylight and that thought cemented my decision.

|

|---|

| The emergency shelter at the top of the pass |

Despite being there for just over 3 hours I only managed around 15 minutes sleep before packing u and setting out into the beautiful dawn which had eluded me under the cover of last night’s darkness.

|

|---|

| A new dawn |

Despite the lack of sleep I felt invigorated by the new day and was looking forward to some hopefully easier ski-Ing than I’d had the previous day, it looked like it was all downhill to hut 2 at Singi.

I began the descent, gentle at first and easily controllable. Then steeper, and steeper and faster – concentrate you’ve got this and for a while I did. And then I didn’t and I was falling. Falling and sliding down the steep slope with my pulk pushing me from behind until I was stopped by the volume of snow.

I cried out in frustration but to no avail - in Europe’s last wilderness no-one can hear you scream. I tried to remain calm, take stock of my situation and considered my options.

Nothing is hurting so hopefully nothing is broken or seriously injured. I am warm and in no immediate danger although the longer I remained here the more my situation would deteriorate.

I can’t press the emergency button on my tracker or send any type of message on it because my tracker is in my pulk and my pulk is busy trying to kill me.

I could get to my phone but there’s no signal for miles around.

I could reach my whistle, attached to one of the arms on my backpack but what use would that be?

Option 1 is stay where I am. How long will it be before anyone comes looking for me? After about an hour my satellite tracker will start beeping because I’m not moving.

I’ve just slept at the top of the pass so there should be no reason for me to have stopped again so soon for so long. Hopefully this should be realized quickly, and a decision made to mobilize some sort of help.

Where will this help come from? If there is another participant near me they will be contacted and asked to assist. I’ve no idea who is left in the race or where they are so I have to rule that out.

There are 3 safety team in a small mountain hut I passed through last night- they could be asked to help. It took me about an hour to get to the top of the pass from this hut earlier this morning. If they come on skis maybe they could be here in around that time, if they don’t have skis and come on foot they will be post holing through deep snow and will take at least double that. They will probably assume I’m immobile or unconscious and will have no way of extracting me. I decide help via this route is unlikely.

The closest road I am aware of is over 30 miles away.

I conclude the most likely assistance will come via Sami on a snowmobile, probably with a medic in tow. How long will this take? The next mountain hut is around 15 miles further down the valley but there’s no road there and they will likely me mobilized from farther afield.

Best case scenario I estimate 3 hours before any help could be here and it could be considerably longer. On the bright side it was unlikely to be 127 hours and no bodily parts should need to be sacrificed.

This is a bad option.

Option 2 try to leverage my legs from under the pulk and try and free myself from its icy grip. This proved impossible they are firmly wedged and going nowhere.

Option 3 – try and push my hands behind my back and unclip the karabiners. This would have to be done one handed without my big mitts so I’d have enough dexterity. I briefly try this but its impossible.

Option 4 was to try and twist around and attempt to unclip the karabiners one by one with both hands. I knew that I had a limited time window to do this as my hands would become cold and numb very quickly outside the protective layer of my big mitts.

It took a considerable amount of effort even just to twist around, as the pulk also twisted with me and was constrained by the snow. I rocked back and forwards to provide some momentum before trying to hold my position and unclip the karabiner. I could open the clip but the force of the pulk pushing down meant I had to exert upward force to attempt to free it.

I lost count of how many times I tried this. Rock back and forth, reach push, try desperately to free the clip. And then after what seemed like an eternity POP it was free!! Get In!!!! Now all I had to do was repeat the procedure on the other side.

After most twisting and turning I finally managed to pop the karabiner and I was free. Sort of.

My legs were still trapped under the pulk at an awkward angle. A desperate struggle ensued involving attempting to push the pulk upwards enough to be able to pull my still ski attached feet from underneath it whist at the same time preventing it from sliding further down the hill.

This was finally achieved, and I could stand up. Or at least I could try.

Standing up with ski’s attached to your feet is difficult at the best of times, but I still had to keep hold of the pulk to prevent it from careering out of control down the steep hillside possibly never to be seen again.

By a significant amount of pulling, pushing and swearing I eventually managed to stand up and manoeuvre the pulk so that it was facing horizontally across the hill and not in any danger of spinning out of control. I took off my ski’s and retrieved my poles. Well one of them, the other was nowhere to be seen presumably buried under the snow somewhere.

After a bit of digging, I managed to find it and then performed the tricky manoeuvre of descending the remaining steep section on foot manually pulling the pulk behind me.

Finally free and down from the steep ground I started to reattach everything, only to discover one of the karabiners was mangled and of no use, crap! Luckily I had a few spares but they weren’t as strong as the broken one, would they hold?

I had no idea but it was my only option so I carefully attached them and hoped for the best whilst wondering if they didn’t if gaffer tape could also be used.

I breathed a sigh of relief and finally progressed on my journey hoping that this would be the biggest issue I’d face in the race. I was wrong about that, but we’ll come to that later.

A long trudge

Now past the steep section I could see the trail stretching out for miles into the distance through a large glacial valley flanked by huge mountains of both sides with views of even bigger mountains far ahead on the horizon. It was a truly mesmerising scene and I felt equal amounts of awe and humility.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t the gradual easy descent I’d been anticipating and I was having to work hard to make progress. There were no snowmobile trails, so I was following the tracks of those in the race who’d went before me although I had no idea who that was. Surprisingly no-one else had stopped at the hut at the top of the pass.

After a while I spotted the shape of a body lying in the snow (thankfully a live one) – it was Andrew. He’d pushed on a bit further than me last night and had now stopped to bivvy out on the trail. We briefly chatted before he attended to his beeping tracker – presumably about the scold him for not informing the safety team of his intention to stop.

A little further on I spotted a tent in which I assumed Robi was resting. There were no signs of life, so I pushed on, not wishing to disturb him.

The excitement and adrenaline of the morning had now long worn off, I was lethargic and felt like I was moving at a snails pace.

I’d lost at least 45 minutes due to my entrapment further up the mountain and my slower than expected pace meant that the 3pm cut-off which at the beginning of the day seemed like a challenging but achievable target now seemed like an impossible one. At my current pace I calculated it would be around 4:30 by the time I reached it.

When you compete in any other type of foot race you have a number of gears available to you, from a slow death march, a brisk walk, slow bimbly run and even flat out sprinting (normally reserved for the last few hundred metres of the race).

It seemed as if I had only one gear and that gear was crawl. Then the trail began to climb again, wtf I thought it was all downhill from the pass, surely this can’t be right? But a quick check of the map revealed that the trail did indeed climb up to flank the hillside before dropping down on the other side to the next hut.

This was a real low point in the race for me, I was going to be timed out before I even reached the first checkpoint. Would they enforce the cutoff? I knew were still people behind me so I wouldn’t be the only one but I just didn’t know. All I knew was that I just had to keep moving forward.

Then to compound matters the weather changed. It started to snow – not heavily but the visibility dropped considerably, and I was soon in a whiteout, being able to see only the red crosses marking the trail in front of me. I couldn’t even make out the trail beneath my feet.

I slowly trudged on and then my tracker began to beep. I performed the slow ritual of manoeuvring to retrieve the tracker from my pulk and read the message.

“Nice try Rob, not a bad effort but unfortunately hut 2 is the end of your race. And really, what were you thinking of entering this race it’s clearly well outside of your capabilities”.

That’s what I was expecting, instead it read

“You are going well, the cut-off at hut 2 has been extended to 5pm keep going”.

Ok so it wasn’t the end of my race after all, I pushed on with a renewed vigour.

Then about 15 minutes it started beeping again. I cursed as I had put it back in my pulk. I carried on going for a few minutes contemplating what information it may contain.

Eventually the beeping was threatening to send me mad and I had to check.

“Competitors will be assessed as hut 2 and if fit will be allowed to continue”.

Ok, I put the tracker in my pocket to avoid any more wasted time pulling it in and out of my pulk.

I was almost at hut 2 when I glanced behind and spotted someone else coming up the trail. I was fully expecting this, Robi, or Andrew had caught me up due to my snail like pace. But no, it was Kev! Wtf

“Hi Kev, you alright” I enquired.

“Aye, I took a wrong turn back there lost a load of time”

“Shit mate, well at least your back on track now”

And so we entered the next hut together and were greeted by the safety team. I asked how many people had been through so far. “None, you’re the first”

Wow, I was flabbergasted as was Kev.

|

|---|

| Arriving at Singi Hut |

We entered a small room with barely enough space to fit us in and performed the usual faffing routine. Eat a dehydrated meal, try and briefly charge my headtorch battery and phone, go to the frozen outdoors long drop toilet. At least this one had a polystyrene seat – luxury!

Kev left a little before me and I followed him out into a 2nd night on the trail just as a few others were arriving.

|

|---|

| Luxury toilet facilities at hut 2 |

A second night on the trail

I caught up with Kev as he was stopping to check his nav. One thing I noticed was that he was wearing short skins on his ski’s whereas mine were full length. That meant climbing was harder and on some of the steeper sections he had to remove his ski’s but on flat ground and downhills he benefited from more glide.

We skied together for a short while before he pulled away and I was again left alone in the silence. Silence apart from the noises from the pulk and from the ski’s – crunch crunch, squeak – I did consider putting on my headphones but it seemed like too much hard work.

With no visual or audible stimulation the going was incredibly monotonous and pulling the pulk was exhausting (I estimate it was around 30kg). The variety you get whilst running over different terrain was missing. It was the same movement, slide one foot forward, then the next. Over and over and over again.

But hey this is what I’ve signed up for, I knew it wasn’t going to be easy.

After a few hours I received a message “CP1 cut-off extended to 1pm. 3km per hour from 7pm” (the cut-off had originally been 9am).

As the previous cut-off had been extended I was expecting the next one to also be extended but it didn’t seem like it was by much and unless I didn’t sleep the chances of me making it in the time were slim to none.

Maybe if it was the end of the race I could have pushed through but I still potentially had over 6 days left, I had to sleep at some point.

I decided by being a bit more efficient I could reduce my pre-race planned rest time down from 6 hours to 4. I had water from the last hut so shouldn’t need to melt snow, so 45 mins each side of camp and 2.5 hours sleep.

The optimal time to do this I decided was between 11-3. It would give equal amounts of darkness either side and was a natural time to sleep and hopefully keep my Circadian rhythm intact.

By 11 I was feeling tired and starting to get a few niggles and pains so that cemented the decision, I picked a spot by the side of the trail and flattened out a patch in the snow with my skis (the snow was too deep to pitch a tent normally).

I opened my pulk to discover my tent covered in ice, shit something had leaked onto it although it wasn’t apparent what.

To save time I thought it would be a good idea to start rehydrating one of my meals with the hot water from one of my flasks whilst I put the tent up. When I did however I noticed the water was only luke warm – at the time I assumed when it had been refilled at the last hut it hadn’t been boiling hot, although on reflection I don’t think this was the case.

It took me longer to put the tent up than I’d anticipated as some of the poles had frozen (due to the spillage). I decided that I needed to re boil the water in my bottles and flasks so that it would last into the following day and I could have another meal in the morning.

Using a liquid fuel stove is very different from a gas stove which you usually just open the valve, light and hey presto you have a roaring flame.

The problem with gas is that it doesn’t perform well, or indeed at all sometimes in sub-zero conditions so liquid fuel stoves are much more reliable and efficient.

First of all you have to pressurise the fuel bottle by pumping it a number of times. The stove then needs to be primed which involves releasing a small about of fuel into a cup that sits beneath the burner and lighting it (I made sure to keep one of my lighters close to my body). This warms the fuel line which then enables the fuel to be vapourised and produce a nice controlled blue flame.

This process is fraught with danger and stoves have a tendency to flare up producing football size fireballs which can instantly reduce tents to ash so it’s a task best done outside.

When I tried to pressurise the fuel bottle there was no resistance on the pump and I assumed that it was fuel that had leaked inside the pulk. I managed to light the stove but it only yielded a pathetic flickering light – it would take forever to heat anything up with that so I turned it off.

At this point Ed passed by, he seemed in good spirits and was heading to try and find a hut a little further down the trail to rest in (I subsequently discovered that he didn’t find it and had a brutal night camping on the trail).

I was trying to eat my ready meal at the same time as doing this, but it was now cold and not very appetising. By the time I retired to the tent to rest the last bits were frozen solid.

An uncomfortable night and a big decision

The tent was on a slight downward slope and the closed cell sleeping mat on which I was lying kept slipping downwards and folding up concertina style at the bottom of the tent. This meant that my top half would be lying directly on the thin canvas floor of the tent – ultimately on snow which was both uncomfortable and cold.

I had put my flask and remaining water bottle inside my sleeping bag to prevent them from freezing and this in turn heightened my discomfort. I put my big mitts inside too to make sure they didn’t freeze.

Without the stove it was freezing inside the tent - my breath was condensing onto the inside of the tent and onto my sleeping bag and instantly turning into ice.

I managed a little more sleep than the previous night, maybe 30 minutes. Upon awakening the first thing I did was to retrieve my mitts from my sleeping bag hoping that they had dried out but I was horrified to discover that they were moist all the way through, shit!!

Upon checking my boots I also found them to be frozen solid and I was unable to even get my feet in them. The zips were jammed frozen and I was unable to move them, and I also noticed small patches of ice on the outsides of each boot around the forefoot area.

Upon further inspection I discovered the stitching was starting to come away at the side of the boots and ice was forming in the gaps.

Despite wearing gloves and keeping my hands inside my sleeping bag all of my fingertips were numb and in particular the middle finger of my left hand was quite sore to touch, although there didn’t seem to be any discolouring and the skin still felt pliable.

Again, I was in a bad situation.

Without a stove I couldn’t dry anything out and I couldn’t let my fingers become cold again.

I felt warm enough inside the sleeping bag, I had plenty food and about 1.5l of water – I was comfortable and in no immediate danger.

I fumbled around with the tracker and sent a message to race HQ “All gloves wet or frozen, stove is broke”

Back came the reply “are you safe and warm”

“Yes, in sleeping bag in tent” I responded.

“Can you confirm if you need assistance”.

I thought for a little before responding.

“Yes” I replied

“We will contact safety team and get back to you”.

I relaxed a little, help was on the way. Or at least it would be. There was nothing else I could really do other than put my head down and try and get some sleep.

After a while another message popped up “Sami on way 3 hours. Bringing gloves and stove. Could you carry on?”

This was a surprise – I’d assumed this was the end of my race there was no way I was going to make the 1pm cut-off (it would be 9:30 before the Sami arrived and I still had over 20 miles to go) but now I was being given an option.

I pondered the question before replying “Yes but won’t make cutoff?”

No reply was forthcoming, the question remained unanswered, and I lay there waiting.

Hours later the roar or a snowmobile engine signalled the arrival of the Sami (He was called Magnus) and he delivered his promised items or a stove, fuel and a pair of big mitts.

I got the stove going as he asked me what I wanted to do. What are my options I asked back.

You can either continue in the race or came back to CP1 with me on a snowmobile. He also told me that other than myself there were only now 2 people left in the race. Wow that was a surprise.

My tracker beeped, “is Sami there? Cut-off has been lifted do you wish to continue?”

Whatever my decision I knew that I had to thaw out my boots enough for me to be able to get my feet into them, so I brought the stove inside the tent, shut to door and carefully held the boots as close to the roaring flame as I dared.

My fingertips were throbbing and numb and I asked Magnus for his opinion. After a cursory glance he replied that just because my fingers are numb it doesn’t mean that I have frostbite, but I’m not a doctor.

I inspected them again myself. They looked normal, there were no white patches or other discoloration and they felt malleable to touch.

Ok, lets think this through.

I now had a stove and a warm pair of gloves so I could melt snow and dry equipment.

It was over 20 miles to CP1 – at my current pace I calculated it would take at least 12 hours to get there, most of it being during the night.

I had some stiffness and niggles but assuming nothing deteriorated then nothing should stop be physically moving. I also had plenty food.

My hands weren’t showing any signs of frostbite but I suspected that I had frostnip (which is the pre-cursor to frostbite) and that meant that under no circumstances could I allow them to become cold again. Could I guarantee that for the next 12 hours? For the next 6 days?

If I made it to CP1 then what next? If was quite clear that the race wasn’t going to finish in Hemavan, but if not there then where? And when? Would it just be a case of keeping moving for 6 more days to see how far I could get? Would there be any more cut-offs?

I wanted Magnus to tell me that I had put in a heroic effort, that I should feel proud of myself for getting this far but that I really should call it a day now rather than putting myself in any more unnecessary danger and risking permanent damage to my hands or worse.

Or maybe I wanted him to tell me to stop being so soft, to get my shit together and get my arse moving – I haven’t got all day to hang around looking at you feeling sorry for yourself you know.

He just stood there staring at me emotionless. I wasn’t going to get any help there this was my decision alone.

Mentally and physically, I wasn’t ready to leave the race but what would my goal now be if I continued? What experiences and learnings could I get from the race that I hadn’t already?

I do what I aways do in these situations and pictured my future self. Would he be happy for me to quit now? Although I was still no-where near the end of the race I’d had a great time and making it to the last 3 felt like some sort of achievement – I’d managed 54 miles in 2 days.

I felt like I hadn’t disgraced myself and not been out of my depth, I’d ultimately been let down by a serious of poor decisions and stupid mistakes which I could learn from.

After about 45 minutes my boots had thawed out enough that I could shoehorn my feet into them with a bit of force, but they were like blocks of ice and I still couldn’t budge the zips to fasten them up, nor could either of the Sami (another had arrived by now, Per-Isak).

That was the final straw I called it, and my race was over.

All that was left to go was to pack up camp and accept the snowmobile ride to CP1.

|

|---|

| The amazing Sami snowmobile team |

White knuckle ride and another fall

I’ve never ridden on a snowmobile before but had always wanted to.

There was no safety briefing, risk assessment or instruction, it was just a case of hop onto the back and cling on for dear life. I jumped on with Per-Isak and Magnus loaded my pulk onto a trailer he was towing on the snowmobile.

I can’t explain how exhilarating that ride was, it was amazing. Over hills, across frozen lakes and skilfully weaving through dense birch forest we sped sometimes at speeds close to 50mph. Vast landscapes opened up all around of soaring mountain ranges vast frozen lakes and huge birch forests. Just when I thought the scenery couldn’t improve, we crested another ridge and the view was even better.

It was a beautifully crisp bluebird day and we were even treated to a stunning Sun Dog.

It was breath-taking and terrifying in equal measures. As one point coming down a steep hill off camber Per-Isak stacked it and we both went flying off landing unhurt in the deep snow. Per-Isak apologised but we both laughed about it before rolling the snowmobile back over and jumping on again.

We stopped en-route to pick up Robi who had also retired from the race and was resting in one of the mountain huts. Further down the trail we also passed Ed and Kev, together and now the only 2 remaining people in the race.

Upon arrival at CP1 at Stora Mountain lodge we were greeted by Phil who kindly looked after us, followed up by Charlotte to give us a medical check.

|

|---|

| Some impressive icicles at CP1 |

She confirmed the frostnip in my fingers but was happy how they responded after re-warming. Robi wasn’t so lucky, she suspected mild frost-bite and advised him to check into the emergency department in the nearest hospital. Apparently another 2 people had suffered the same fate.

Dean kindly drove us to the nearest towns from which we could plan our return journeys. For me that was spending the night in Gallivere before a 17 hour train journey to Stockholm and subsequent flights back to Newcastle. For Robi it was Kiruna where he planned to check into the hospital there.

Epilogue

I write this around 2 weeks post-race. Some of my fingers are still numb but other than that physically I’m fine.

I enjoyed following the remainder of the race, with a slight pang of sadness that I was no longer in it.

It was a brave decision for Ed to leave the safety of his team and push on solo, and he was rewarded with a Challenger finish in Kvikkjokk, 127 miles.

Kev pushed on solo for the remainder of the race and was credited with a finish at the re-scheduled finish in Yakkvik, 185 miles, a superb effort.

I’m sure he would still be out there now if he hadn’t been stopped.

I feel incredibly privileged to have been a part of the inaugural race, the overall experience is like nothing I’ve done before and is one of the highlights of my life. It has really been a race of so many extremes.

I’ve witnessed some of the most breath-taking and remote landscapes I’ve ever seen, I’ve endured the lowest temperatures I’ve ever been exposed to and faced more challenges than I have in any other race.

There have been many hours of solitude, but I’ve also shared experiences with some amazing people both fellow competitors and also the race staff.

As I mentioned earlier this race in unique in its combination of expedition and race skills. Kev has set a high bar, and it will certainly be difficult to eclipse. I do believe however that over time people will become more adept and combining the necessary skills, also with the benefit of previous races to draw from and the standard will be pushed forwards, as it has with all other races.

Lessons learned and what I will do differently next time.

You can read all the books and watch all the video’s but sometimes you must learn from making your own mistakes (as long as they aren’t serious mistakes as you don’t learn much if you’re dead).

Looking back now some of the mistakes I made seem trivial and it’s hard to understand how I could have made them.

The ice on my tent couldn’t have possibly been fuel which had leaked from the bottle because fuel doesn’t freeze at those temperatures. Otherwise, if would freeze inside the bottle, and I would have surely been able to smell it.

If I’d realised this, I would have also realised that my fuel bottle was still full, so I could have tried to address the issue with my pump. I suspect that the lack of friction was due to the rubber losing elasticity in the cold conditions and thus not providing sufficient pressure. I could have tried warming it next to my body and lubricating the plunger.

I’ve since discovered (thanks to John Bamber) that you can but pumps specially designed for sub-zero temperatures so I will certainly be investing in one.

In retrospect I believe it was my flask which had leaked which would also explain the luke warm water in it. Alex had commented back in hut 2 when he filled it up that the top wasn’t closed snugly which is something I’ve noticed before, but it’s never leaked. Until the exact moment I didn’t want it to leak.

Most importantly I need to manage my hands better and not let them get as cold as they did on so many occasions. More use of hand warmers, wearing water vapour barrier gloves (i.e. surgical gloves) and keeping my gloves close to me when not in use.

Similarly wearing water vapour barrier socks will prevent sweat getting into my boots. I did have a pair of WVB socks with me but they didn’t feel comfortable, and I was concerned about blisters so I chose not to wear them which turned out to be a mistake.

|

|---|

| Fingers post race |

I’d also try to utilise the huts (if open and not snowed in) more as opposed to camping in the snow although this is only possible in certain areas of the trail.

Will I be back next year for another go?

Of course I will be. This experience has only made me more hungry to return to these spectacular landscapes.

Write up on the training course

Will Roberts collared me for a few words post-race which you can view below

There are more video’s on the race on the Spine YouTube channel here

Thanks to Will Roberts and Bjorn Sorensen Trailbear Films for use of their photos

Kit

Boring bit on what kit I used for the race:

Feet

Alpina Outlander BC boots. I really liked the boots however they both started to split along the seams on both sides after day 2. I’ve since spoken to the shop and they think it’s because the boot has too much volume for my feet and hence was flexing more and putting more pressure on the stitching.

Merino wool socks. My feet were never cold during the race, however the reason my boots froze on day 2 was because too much sweat had permeated into the boot. In future I will be wearing water vapour barrier socks.

Montane Phase Waterproof gaiters

I chose to ski and pulled a plastic pulk with a metal trace and I believe this was the right option as opposed to snow shoes. Interestingly Barclay had a full ski touring setup with a backpack instead of pulk and this seemed to work well for him.

Legs

Dare 2 B Salopettes

Running shorts

I also carried a pair of thermal leggings but didn’t wear then in the race my legs were never cold.

Montane Terra Pants (not worn)

Top

Alpkit Kepler merino wool base layer

OMM Mid Layer

Montane Protium Hoodie

Montane Ajax GORE-TEX Jacket

Alpkit Fantom Down Jacket

Head

North Face beanie hat

Numerous buffs

Cold avenger

Balaclava

Goggles

Hands

Wrist warmers

Thin liner glove

Black Diamond Legend leather gloves

DexShell ThermFit Waterproof Gloves

Montane Alpine 850 Down Mitts

I found the best combination to be wrist warmers, a thin liner gloves, the Dexshell gloves with the big mitts over the top. In the future I’ll also be wearing a thin surgical glove to prevent sweat permeating into my gloves (and then freezing)

Camp/cook

Hilleberg Soulo BL tent

North Face Inferno -40 sleeping bag

Alpkit Hunka bivvy bag

Closed cell sleeping mat

MSR Whisperlite International Stove & maintenance kit

Home made stove board

Fire Maple kettle

Snow Shovel

Leatherman Signal multitool

Electronics

Iphone - no signal anywhere en-route but battery held out for photos

Intu 20,000mAh power bank

Peztl Actik Core Head torch *2

Garmin 64s with talky toaster maps installed

Garmin Epix Pro 2 watch

I only needed 100 lumens brightness the majority of the time. Used watch for nav the majority of the time in combination with the map. Never needed to use the 64s

Water and carrying capacity

1l Stanley Flask 500ml Thermos food flask 2 * 1l Nalgene bottles, 1 with insulated sleeve

Water froze too easily in the Nalgene’s and I didn’t have time to keep topping them up with warm water from the flask. Better solution would be a larger flask and 1 Nalgene (with insulated sleeve).

I wore a 25L OMM rucksack at all times with equipment/food I thought I’d need quickly to save having to open the pulk. This ended up being a pain as the straps often got tangled with those of the harness, and also the straps on my gloves. A better system would have been a large bum bag and putting my large insulated jacked in my pulk (although I ended up wearing it anyway).